At work, I typically sit at an east-facing window on the 35th floor of the Sears Willis Tower. Here's my view:

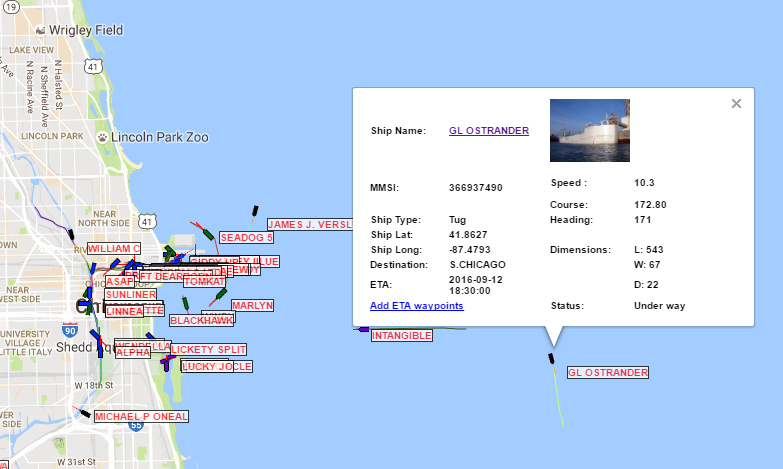

That means I can often see Michigan, Indiana, and everything in between, including very large boats out on the Lake. For the last half-hour I've watched a huge white thing slowly steam South, wondering what it was. It turns out, there's a website for that. And the boat is, in fact, pretty big:

So the 138-meter Glostrander is puttering southward at 19 km/h towards South Chicago. Good to know. (You can see the boat in the photo above just to the left of the Board of Trade building. It's the white horizontal sliver close to the horizon.)

Usually I just link to articles I haven't read yet. This morning, here's a list of videos friends have posted. (They take longer than articles.)

And, OK, one article: Politico interviewed dozens of people who were involved with getting the president home on 9/11, fifteen years ago today. Their accounts are riveting.

Two stories, in two directions. First, a cool interactive history of how the construction of Chicago's Eisenhower Expressway (I-290) displaced thousands of people and destroyed thousands of buildings:

In the late 1940s, the Oak Leaves newspaper in Oak Park predicted that the new superhighway would replace the West Side’s “appalling slums” with “orderly dwellings where orderly people are living in health and comfort.”

Of all the neighborhoods that the expressway sliced through, the Near West Side had the largest population of blacks in 1950. Nearly 40 percent of its people were African-American.

In February 1949, city housing coordinator D.E. Macklemann said some people in the neighborhood simply didn’t believe that the highway would actually get built. “One man forced us to get an eviction order from the court because he said he had been reading about superhighways for years and thought the whole thing was a dream,” Macklemann told the Tribune. “In several instances residents paid no attention until the buildings next door were being torn down.”

Second, a report about how Rochester, N.Y., has followed San Francisco, Boston, and other cities in burying or removing highways that blighted or isolated their downtowns:

Rochester lucked out. The eastern quadrant of the Inner Loop was isolated from the main flow of traffic into the city, and thus, the traffic volume on that segment of highway was never particularly high. As a result, discussions about burying this portion of the Inner Loop weren’t sidetracked by circular debates about what to do with the traffic it would displace. It may have taken decades to move forward, but that’s still more progress than many cities can claim.

Our research at the University of Connecticut shows that cities that transformed their downtowns with freeways, parking, and monolithic developments were flooded with traffic even while they were losing jobs and residents. The few American cities that maintained most of their prewar urban fabric saw much less growth in traffic congestion and have retained their character as vibrant walking cities.

We also know that cities that have removed freeways—usually due to an act of nature—have seen a decrease in traffic congestion. In some cases, the decrease was more than 50 percent.

I hope that someday, years from now but in my lifetime, we'll see the Eisenhower buried as well. There have been proposals to do that in Oak Park almost since it was built. But that would require a commitment to livable spaces that the U.S. doesn't seem likely to make.

So, this happened on my train line:

A Metra train on the Union Pacific North Line was struck by lightning Tuesday morning in the Rogers Park neighborhood on the North Side.

Outbound train No. 309, scheduled to arrive in Kenosha at 8:18 a.m., was stopped shortly before 7:30 a.m. when it was struck by lightning, causing a mechanical failure near the Rogers Park Station...

Metra spokesman Tom Miller said no injuries were reported.

It actually only added about 15 minutes to my commute. Of course, if I'd known about the problem before seeing two outbound trains copulat--er, coupled together at my station while walking there (in the rain), I'd have taken the El.

At least it wasn't raining hard.

The UK's Daily Mail has a decent explanation and creepy photos of how the southernmost city in Illinois went from a thriving (and historical) port to a nearly-abandoned shell in 50 years:

The town's luck began to fall in 1889 when the Illinois Central Railroad bridge opened over the Ohio River - although much railroad activity was still routed through the town, so its effects were not severe.

The same can't be said for a second bridge that opened around 23 miles up the Mississippi at Thebes, Illinois in 1905.

The completion of that bridge drained away much railroad activity, reducing the need for the ferries that once carried railroad stock.

And with steamboats being phased out in favor of barges, Cairo was no longer the essential hub it had once been. The end had begun.

The town was hit again in 1929 and 1937 when bridges were completed across the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, respectively, allowing a route through for US Routes 51, 60 and 62.

As the bridges were built at the town's southern tip, it was easy for traffic to bypass Cairo completely, draining away more money.

But there was still a little money coming to the town until 1987, when the Interstate 57 bridge opened across the Mississippi, allowing traffic to bypass the town altogether - killing its hotel and restaurant industries.

I visited Cairo in 2003. It was pretty dead then, but judging by the photos in the Daily Mail article, it's even worse now.

Here's the confluence of the rivers, in December 2003:

Ah, I can finally take a few minutes to read through my backlog of articles, which have a common theme coming off this past week's events:

That, plus a tour of the Laguintas Brewery this afternoon (the one here, not the one in Petaluma), ought to keep me busy.

Oh, Wisconsin. You gave the world Robert La Follette, but also Joseph McCarthy; Frank Zeidler, and Paul Ryan; and, of course, Scott Walker, whose latest rigidly-ideological imbecile move will keep Wisconsin firmly in the 20th century:

Gov. Scott Walker’s decision to hand back $810 million to the federal government — money that would have built a fast train from Madison to Milwaukee and Chicago — remains one of the most unfortunate and stupid acts in recent Wisconsin history. Not only did Walker deprive Wisconsin of a modern rail system, his ideological rigidity cost our state thousands of jobs and tens of millions of dollars.

Walker’s decision, supposedly based on avoiding about $5 million a year in operating costs, has cost the taxpayers plenty. Because the federal grant would have made necessary repairs to the Hiawatha line from Milwaukee to Chicago, returning the federal money has meant that the state has had to spend tens of millions of Wisconsin taxpayer dollars instead. The cancellation of the rail link also meant that the state was out $50 million to the train manufacturer Talgo for trains that were built but never used, plus a large punitive settlement.

It wasn’t just tax dollars we lost. In a state that has fallen behind the rest of the nation in job creation, we also forfeited a large number of employment opportunities. According to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, rail-related employment would have peaked at 4,732 jobs, largely in construction of the line. Operating and maintaining the trains would have created 55 permanent jobs. On top of that, the train manufacturer Talgo laid off its workforce and moved out of state. Talgo employed 150 workers in a section of Milwaukee that desperately needs jobs and held promise to expand future employment significantly. Also, a modern transportation system is a big draw for high-tech companies.

Progressive administrations are also draws for high-tech companies (or, rather, their employees), as North Carolina is finding out.

I wonder if voters will ever figure out that the Republican Party is killing their economic opportunities every chance they get?

The Swiss have built a 57 km tunnel under the Alps, and it opens June 1st:

[T]he new Gotthard Base Tunnel burrows deep beneath the mountains to connect Switzerland’s German- and Italian-speaking regions, ultimately linking the Swiss lowlands with the North Italian plain. It exceeds the length of its longest predecessor, Japan’s Seikan Tunnel, by a little over three kilometers (1.9 miles). Running at up to 8,000 feet below mountain peaks at times, it also runs deeper below ground level than any other tunnel yet built. So great is the amount of rock and rubble created by the excavation—over 28 million tons—that steep artificial hills have been created in the valleys at the tunnel’s mouth.

Now that trains will run on a specially constructed, almost entirely flat track, trains through the tunnel will be able to reach speeds of 150 miles per hour. This will slash the journey time between Zurich and Milan to just two hours and 30 minutes, considerably faster than the current four hours and 40 minutes. While that’s impressive, shorter hops between sub-Alpine cities aren’t really the new tunnels main raison d’etre, and wouldn’t alone necessarily be worth an injection of over $10 billion.

Why is Europe in generally better shape even though their economy is technically in worse shape? This might be an example.

Engineer Jeff Speck is dismayed that his home town, Lowell, Mass., is planning to replace an unattractive and un-walkable street with an equally-un-walkable design:

Imagine my surprise, then, when I came across an article earlier this month about the city’s plans for its southern gateway, the Lord Overpass. This site is particularly important to Lowell, being an area of major redevelopment as well as the key link from the train station (at right in the image below) to downtown (beyond the canal to the left). This collection of streets—a squared traffic circle floating above a highway—is due for reconstruction, and the city came up with the smart idea of putting the depressed highway back up at grade to create more of an urban boulevard condition.

So, let’s zoom in and describe what we see:

- Four lanes dedicated to motion straight through, just like the now-submerged highway;

- Three lanes dedicated to turning motions, two of which swoop around the edges in great curves;

- Two dedicated bus lanes, each about 17 feet wide, curb-to-curb. (A bus is 8 1/2 feet wide, so perhaps the goal is to squeeze two past each other?);

- Bike lanes that are partly protected, partly unprotected, and partly merged into the bus lanes;

- A collection of treeless concrete wedges, medians, and “pork chops” directing the flow of vehicles;

- No parallel parking on either the main road or any of the roads intersecting it; and

- Green swales lining the streets, resulting in set-back properties to the one side and open space to the other. (Note that the open space at the bottom of the drawing is too shallow to put a building on.)

The engineering drawings are horrifying. As Speck says, to the engineering firm Lowell hired, everything looks like a nail.

Here we go:

It's also a nice day outside, so Parker will probably get two hours of walks in.