Sullivan raves about how New York's political leaders in both parties have made gay marriage a real possibility this year:

It's a BFD because it doubles the number of Americans with the right to marry the person they love, even if they are gay. That is one hell of a fact on the ground. It will almost certainly help in California. It will reveal even more profoundly that this does not mean the end of civilization, but is, more prosaically, a modest reform to strengthen the family, integrate the marginalized and enlarge our moral universe. And it cannot now be undone.

Fingers crossed.

The Guggenheim Museum, 31 December 2000:

ISO-100, 1/125 at f/4, Kodak DC4800, 12mm, taken here.

I mentioned a while ago that only with my Canon 7D have I gotten digital images with about the same resolution as film. Even though I made this photo on a 3Mpx camera, I shot it at 1536x1024 because I had, I think, a 64 MB card in the camera, which could hold only about 300 shots. Still, the shot looks decent enough at Web resolutions.

I spent part of the weekend organizing photos from the last decade in Adobe Lightroom. From late 2003 to 2006 I used a Nikon E2100, a little throwaway camera, and I almost cried comparing its photos to the Kodak DC4800's (like the one above) and photos from the Canon SD400 that followed it. The lack of resolution and exposure control gave me more than two years of photos with less quality than shots from most modern mobile phones.

At a campaign rally in Burlington, Vt., 26 September 1992:

Kodachrome 64, exposure unrecorded, Canon T-90 probably with Tamron 35-210mm at 35mm.

I'm not sure if this worked, but I liked the shot anyway. Trump Tower is on the right; the Equitable Building is on the left:

17 June 2011, ISO-100, 1/250 at f/5.6, 55mm, taken here.

Last one from Lisbon, on the plaza surrounding the Castelo de São Jorge:

13 January 2011, ISO-400, 1/250 at f/8, 55mm, here.

In honor of Parker's birthday:

1 October 2006, ISO-400, 1/200 at f/5.6, 18mm, Evanston, Ill.

The fuzzy dude turns 5 today:

Parker's Petfinder mugshot, at 8 weeks old.

Andrew Binstock, editor of Dr. Dobb's, has a pair of editorials in praise of and instruction to create small classes:

High levels of complexity, generally measured with the suboptimal cyclomatic complexity measure (CCR), is what the agile folks correctly term a "code smell." Intricate code doesn't smell right. According to numerous studies, it generally contains a higher number of defects and it's hard — sometimes impossible — to maintain. ...

My question, though, is how to avoid creating complexity in the first place? This topic too has been richly mined by agile trainers, who offer the same basic advice: Follow the Open-Closed principle, obey the Hollywood principle, use the full panoply of design patterns, and so on. All of this is good advice; but ultimately, it doesn't cut it. ...

...[Y]ou need another measure, one which I've found to be extraordinarily effective in reducing initial complexity and greatly expanding testability: class size. Small classes are much easier to understand and to test.

In Part 2, in which Binstock responded to people who had written him about the first editorial:

Coding classes as diminutive as 60 lines struck other correspondents as simply too much of a constraint and not worth the effort.

But it's precisely the discipline that this number of lines imposes that creates the very clarity that's so desirable in the resulting code. The belief expressed in other letters that this discipline could not be consistently maintained suggests that the standard techniques for keeping classes small are not as widely known as I would have expected.

Both editorials make excellent points. Every developer should read them.

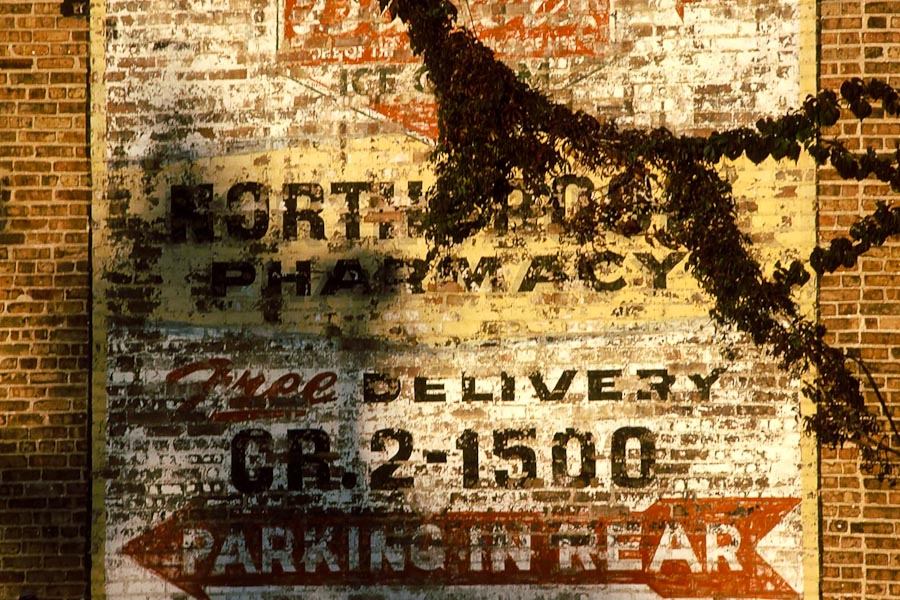

I've always thought this photo looked cool:

October 1985, Northbrook, Ill., Kodachrome-64.

Adam Mansbach's new book hasn't hit stores yet, but already Audible.com has it available for (free!) download, narrated by—wait for it—Samuel L. Jackson.

Adam Mansbach's new book hasn't hit stores yet, but already Audible.com has it available for (free!) download, narrated by—wait for it—Samuel L. Jackson.

Brilliant. Feckin' brilliant.