Bruce Schneier says that the TSA's thoughts about security at smaller airports are exactly the conversation they should be having:

Last week, CNN reported that the Transportation Security Administration is considering eliminating security at U.S. airports that fly only smaller planes -- 60 seats or fewer. Passengers connecting to larger planes would clear security at their destinations.

To be clear, the TSA has put forth no concrete proposal. The internal agency working group's report obtained by CNN contains no recommendations. It's nothing more than 20 people examining the potential security risks of the policy change. It's not even new: The TSA considered this back in 2011, and the agency reviews its security policies every year.

We don't know enough to conclude whether this is a good idea, but it shouldn't be dismissed out of hand. We need to evaluate airport security based on concrete costs and benefits, and not continue to implement security theater based on fear. And we should applaud the agency's willingness to explore changes in the screening process.

There is already a tiered system for airport security, varying for both airports and passengers. Many people are enrolled in TSA PreCheck, allowing them to go through checkpoints faster and with less screening. Smaller airports don't have modern screening equipment like full-body scanners or CT baggage screeners, making it impossible for them to detect some plastic explosives. Any would-be terrorist is already able to pick and choose his flight conditions to suit his plot.

And just think, it's only taken 15 years and $45 billion to get here...

On 8 August 1988, the Chicago Cubs played their first night game at Wrigley Field. The Tribune rounds up memories from people who supported and opposed the installation of lights at the park:

Ryne Sandberg, Cubs second baseman, 1982-1997: Leading up to ’88, the talk within the organization was that lights were necessary to create a schedule more conducive to resting the home team, getting us out of the sun. Before that, with some of those 10-day homestands with all day games (it was) in 90-plus temperatures.

Rick Sutcliffe, Cubs pitcher, 1984-1991: There's nothing better than playing a day game and going home to have dinner with your family. But when you come back from a West Coast trip, and let’s say you had a long game … sometimes we went straight from the airport to the ballpark. It’s really difficult that whole homestand. You just feel wiped out. … I would throw nine innings at Dodger Stadium and might lose anywhere from 2 to 4 pounds. There were times at Wrigley Field during that heat that I lost 10 to 15 pounds. I would love to go start a game to lose 15 right now!

Did lights help the Cubs? Probably; but there's no definitive way to say.

Yesterday was the 73rd anniversary of our nuclear attack on Hiroshima, Japan. On the event's 50th anniversary, The Atlantic asked, "Was it right?"

I imagine that the persistence of that question irritated Harry Truman above all other things. The atomic bombs that destroyed the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki fifty years ago were followed in a matter of days by the complete surrender of the Japanese empire and military forces, with only the barest fig leaf of a condition—an American promise not to molest the Emperor. What more could one ask from an act of war? But the two bombs each killed at least 50,000 people and perhaps as many as 100,000. Numerous attempts have been made to estimate the death toll, counting not only those who died on the first day and over the following week or two but also the thousands who died later of cancers thought to have been caused by radiation. The exact number of dead can never be known, because whole families—indeed, whole districts—were wiped out by the bombs; because the war had created a floating population of refugees throughout Japan; because certain categories of victims, such as conscript workers from Korea, were excluded from estimates by Japanese authorities; and because as time went by, it became harder to know which deaths had indeed been caused by the bombs. However many died, the victims were overwhelming civilians, primarily the old, the young, and women; and all the belligerents formally took the position that the killing of civilians violated both the laws of war and common precepts of humanity. Truman shared this reluctance to be thought a killer of civilians. Two weeks before Hiroshima he wrote of the bomb in his diary, "I have told [the Secretary of War] Mr. Stimson to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.

" The first reports on August 6, 1945, accordingly described Hiroshima as a Japanese army base.

This fiction could not stand for long. The huge death toll of ordinary Japanese citizens, combined with the horror of so many deaths by fire, eventually cast a moral shadow over the triumph of ending the war with two bombs.

It's a sobering essay. It's also a good argument, indirectly, in favor of making sure nuclear weapons are never used again.

Via Schneier, the head of security for the marketing firm running the game stole the million-dollar game pieces:

[FBI Special Agent Richard] Dent’s investigation had started in 2000, when a mysterious informant called the FBI and claimed that McDonald’s games had been rigged by an insider known as “Uncle Jerry.” The person revealed that “winners” paid Uncle Jerry for stolen game pieces in various ways. The $1 million winners, for example, passed the first $50,000 installment to Uncle Jerry in cash. Sometimes Uncle Jerry would demand cash up front, requiring winners to mortgage their homes to come up with the money. According to the informant, members of one close-knit family in Jacksonville had claimed three $1 million prizes and a Dodge Viper.

When Dent alerted McDonald’s headquarters in Oak Brook, Illinois, executives were deeply concerned. The company’s top lawyers pledged to help the FBI, and faxed Dent a list of past winners. They explained that their game pieces were produced by a Los Angeles company, Simon Marketing, and printed by Dittler Brothers in Oakwood, Georgia, a firm trusted with printing U.S. mail stamps and lotto scratch-offs. The person in charge of the game pieces was Simon’s director of security, Jerry Jacobson.

Dent thought he had found his man. But after installing a wiretap on Jacobson’s phone, he realized that his tip had led to a super-sized conspiracy. Jacobson was the head of a sprawling network of mobsters, psychics, strip-club owners, convicts, drug traffickers, and even a family of Mormons, who had falsely claimed more than $24 million in cash and prizes.

The longish read is worth the time.

Sediment under Lake Chichancanab on the Yucatan Peninsula has offered scientists a clearer view of what happened to the Mayan civilization:

Scientists have several theories about why the collapse happened, including deforestation, overpopulation and extreme drought. New research, published in Science Thursday, focuses on the drought and suggests, for the first time, how extreme it was.

[S]cientists found a 50 percent decrease in annual precipitation over more than 100 years, from 800 to 1,000 A.D. At times, the study shows, the decrease was as much as 70 percent.

The drought was previously known, but this study is the first to quantify the rainfall, relative humidity and evaporation at that time. It's also the first to combine multiple elemental analyses and modeling to determine the climate record during the Mayan civilization demise.

Many theories about the drought triggers exist, but there is no smoking gun some 1,000 years later. The drought coincides with the beginning of the Medieval Warm Period, thought to have been caused by a decrease in volcanic ash in the atmosphere and an increase in solar activity. Previous studies have shown that the Mayans’ deforestation may have also contributed. Deforestation tends to decrease the amount of moisture and destabilize the soil. Additional theories for the cause of the drought include changes to the atmospheric circulation and decline in tropical cyclone frequency, Evans said.

What this research has to do with the early 21st Century I'll leave as an exercise for the reader.

When I get home tonight, I'll need to read these (and so should you):

And now, I'm off to the Art Institute.

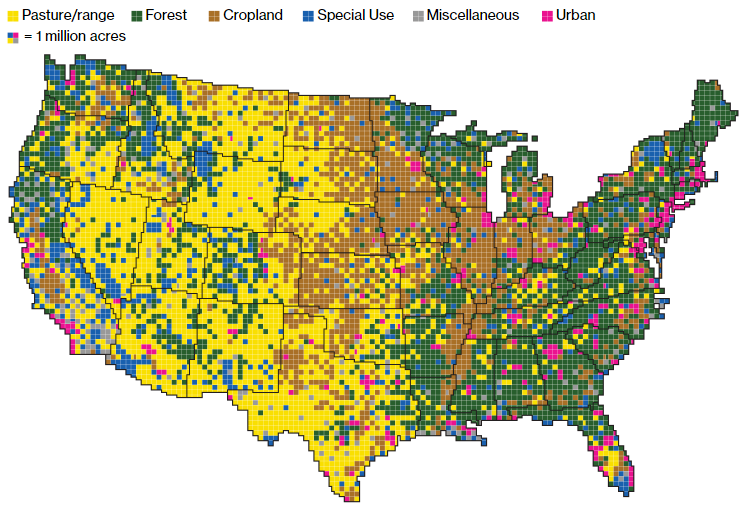

Bloomberg published on Monday a super-cool analysis of U.S. land use patterns:

Using surveys, satellite images and categorizations from various government agencies, the U.S. Department of Agriculture divides the U.S. into six major types of land. The data can’t be pinpointed to a city block—each square on the map represents 250,000 acres of land. But piecing the data together state-by-state can give a general sense of how U.S. land is used.

Gathered together, cropland would take up more than a fifth of the 48 contiguous states. Pasture and rangeland would cover most of the Western U.S., and all of the country’s cities and towns would fit neatly in the Northeast.

This is, of course, total Daily Parker bait.

Happy August! (Wait, where did April go?)

As I munch on my salad at my desk today, I'm reading these stories:

And finally, a bit of good news out of Half Moon Bay, Calif. The corporate owner of the local paper told them they had to shut down, so a group of townspeople formed a California benefit corporation to buy the paper out.

On this day in 1850, Chicago had its first (sort-of) professional opera performance. It wasn't exactly up to the Lyric's standards:

In New York, P.T. Barnum was paying Jenny Lind—“The Swedish Nightingale”—$1,000 a night to perform. Chicago’s first opera didn’t have Jenny Lind. But the local promoters were crafty enough to choose one of her biggest hits for their first show, at Rice’s Theatre. The opera was Bellini’s La Sonnambula.

Four singers are not enough for an opera. So the Chicago cast was filled out with local amateurs. A few of them had good voices, most of them didn’t. Rehearsals were—I think “confused” is a good word to describe them.

Just like in one of those bad old Hollywood movies, the show had problems. The audience kept applauding at the wrong time—whenever one of the hometown amateurs showed up on stage, his friends in the audience would stand up and cheer. Meanwhile, one of the extras named J.H. McVicker sang so loudly he drowned out everybody else.

It helps to remember that 18 years after the city's founding, it more resembled a frontier town than the international metropolis it became in the 20th century. Still, it sounds like a fun show.

And then the theater burned down the next day...

More data has emerged about Amelia Earhart's final days:

Across the world, a 15-year-old girl listening to the radio in St. Petersburg, Fla., transcribed some of the desperate phrases she heard: “waters high,” “water’s knee deep — let me out” and “help us quick.”

A housewife in Toronto heard a shorter message, but it was no less dire: “We have taken in water . . . we can’t hold on much longer.”

That harrowing scene, the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) believes, was probably one of the final moments of Earhart’s life. The group put forth the theory in a paper that analyzes radio distress calls heard in the days after Earhart disappeared.

Some of Earhart’s final messages were heard by members of the military and others looking for Earhart, Gillespie said. Others caught the attention of people who just happened to be listening to their radios when they stumbled across random pleas for help.

Almost all of those messages were discounted by the U.S. Navy, which concluded that Earhart’s plane went down somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, then sank to the seabed.

[Research director Ric] Gillespie has been trying to debunk that finding for three decades. He believes that Earhart spent her final days on then-uninhabited Gardner Island. She may have been injured, Noonan was probably worse, but the crash wasn’t the end of them.

Gardner Island, now called Nikumaroro, fits the classic description of a desert island: it's a small atoll with trees and a very long swim to the next nearest land mass. Crashing there might have meant a slow death from dehydration instead of a quick one from impact. We'll never know for sure, but this new data, if accurate, adds some weight to the hypothesis that Earhart crashed on Nikumaroro in 1937.