...but the Department of Justice suing to block the American-US Airways merger was sure stupid. Cranky Flyer gives them a Crazy Jackass award:

It really does appear that DOJ has gone off the rails. The best way to sum up the argument is that airlines should all be punished for trying to be successful enterprises. The complaint is filled with talk about how capacity has shrunk and fares have risen. They think this merger will result in more of the same. But what they’ve failed to recognize is that the airline industry of the past was a sickly mess. You had too many cooks in the kitchen and some of them had the cooking skills of a 12-year-old. So airlines pushed in too much capacity just to gain market share, then they had to discount fares and nobody made money. It was a mess.

Apparently the DOJ likes that plan. It’s sad to think this is how the government looks at private industry. If you want to decide that the airline industry is a public utility, then go all-in and fully regulate it. (Fares will rise, but I would respect the argument.) Otherwise, this nanny-state-style semi-regulation will keep the industry from ever becoming truly healthy.

The Economist takes a more sober view, but still doesn't think the suit makes sense:

The DoJ suit mentions the likely loss of US Airways’ low fares, known as Advantage Fares, which undercut those of American, Delta and United on one-stop trips and which have prompted US Airways’ competitors to reduce their prices. The DoJ has been scrutinising the merger since January, a month before it was announced publicly. Last week the European Commission nodded the deal through after a minor concession on slots at London’s Heathrow. But the DoJ said the merger would take consolidation too far, leaving four airlines controlling over 80% of the American market.

Doug Parker, the chief executive of US Airways, still hopes the deal can be completed before the end of the year. If it is not, American will struggle longer to emerge from Chapter 11 bankruptcy, as it would have to assemble and seek court approval for a new rescue plan. The existing one was relatively generous to creditors and shareholders, leaving the latter with a stake in the merged carrier. If the courts uphold the DoJ’s view, some observers think it will have the effect of intensifying the dominant position of United and Delta, leading to more losses and later pressure for more mergers—an unintended consequence of the DoJ’s stance.

The DoJ has come down firmly on the way to solve the consolidation problem that will result in the worst deal for consumers. Having three giant airlines doesn't end competition, but it does make it easier to circumvent existing competition rules. The DoJ should concentrate on the actual effects of the proposed arrangement, not on its hypothetical effects, especially when their hypotheses don't actually have a lot of evidence supporting them.

As expected, the Justice Department and several states' attorneys general have challenged the American-USAirways merger:

The Justice Department says the deal would result in the creation of the world’s largest airline and that a combination of the two companies would reduce competition for commercial air travel in local markets and would result in passengers paying higher airfares and receiving less service.

On Tuesday, Attorney General Eric Holder said the transaction between US Airways and American would result in “higher airfares, higher fees and fewer choices.”

The attorneys general were from Arizona, Florida, the District of Columbia, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

The challenge won't succeed, but the AGs had to make it anyway. (Note that Arizona is headquarters of USAirways and Texas is headquarters of American.) The problem is, if American doesn't merge with USAirways, then it's toast—and USAirways will get a hunk of its assets anyway.

I may not have conducted the same analysis as the AG, but I concluded long ago that for me personally the merger works out pretty well. I admit, that may not be true for people who live in smaller aviation markets.

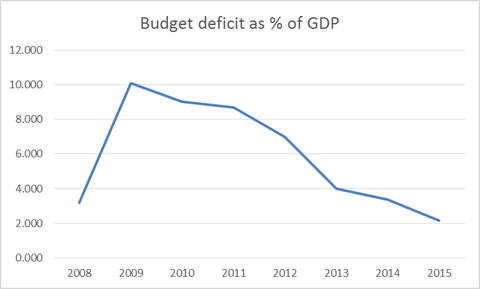

Paul Krugman points out this simple fiscal truth, along with polling data that makes my head hurt:

A little while back I expressed a desire to see a poll of voters asking whether they knew about the plunging federal budget deficit. Just as a reminder, here’s what the CBO numbers for the recent past and projections for the near future look like:

Well, Hal Varian of Google got in touch with me, and said,”We can do that!” So he put together a Google Consumer Survey; it’s still ongoing — results here — but here’s what it looked like this morning:

Excellent work, Republicans. You've managed to confuse about half the public, and in so doing, you've made people favor policies that keep rich people rich and poor people poor.

Can someone with a newspaper please bring reality back into public discourse?

Bruce Schneier thinks the NSA's plan to fire 90% of its sysadmins and replace them with automation has a flaw:

Does anyone know a sysadmin anywhere who believes it's possible to automate 90% of his job? Or who thinks any such automation will actually improve security?

[NSA Director Kieth Alexander is] stuck. Computerized systems require trusted people to administer them. And any agency with all that computing power is going to need thousands of sysadmins.

Some of them are going to be whistleblowers.

Leaking secret information is the civil disobedience of our age. Alexander has to get used to it.

The agency's leaks have also forced the president's hand by opening up our security apparatus to public scrutiny—which he may have wanted to do anyway.

Security guru Bruce Schneier warns about the lack of trust resulting from revelations about NSA domestic spying:

Both government agencies and corporations have cloaked themselves in so much secrecy that it's impossible to verify anything they say; revelation after revelation demonstrates that they've been lying to us regularly and tell the truth only when there's no alternative.

There's much more to come. Right now, the press has published only a tiny percentage of the documents Snowden took with him. And Snowden's files are only a tiny percentage of the number of secrets our government is keeping, awaiting the next whistle-blower.

Ronald Reagan once said "trust but verify." That works only if we can verify. In a world where everyone lies to us all the time, we have no choice but to trust blindly, and we have no reason to believe that anyone is worthy of blind trust. It's no wonder that most people are ignoring the story; it's just too much cognitive dissonance to try to cope with it.

Meanwhile, at the Wall Street Journal, Ted Koppel has an op-ed warning about our over-reactions to terrorism:

[O]nly 18 months [after 9/11], with the invasion of Iraq in 2003, ... the U.S. began to inflict upon itself a degree of damage that no external power could have achieved. Even bin Laden must have been astounded. He had, it has been reported, hoped that the U.S. would be drawn into a ground war in Afghanistan, that graveyard to so many foreign armies. But Iraq! In the end, the war left 4,500 American soldiers dead and 32,000 wounded. It cost well in excess of a trillion dollars—every penny of which was borrowed money.

Saddam was killed, it's true, and the world is a better place for it. What prior U.S. administrations understood, however, was Saddam's value as a regional counterweight to Iran. It is hard to look at Iraq today and find that the U.S. gained much for its sacrifices there. Nor, as we seek to untangle ourselves from Afghanistan, can U.S. achievements there be seen as much of a bargain for the price paid in blood and treasure.

At home, the U.S. has constructed an antiterrorism enterprise so immense, so costly and so inexorably interwoven with the defense establishment, police and intelligence agencies, communications systems, and with social media, travel networks and their attendant security apparatus, that the idea of downsizing, let alone disbanding such a construct, is an exercise in futility.

Do you feel safer now?

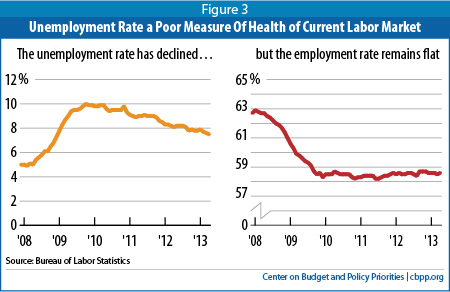

Ezra Klein points to this graph and raises the question:

The core issue here is that the unemployment rate only counts people actively looking for work. That means there are two ways to leave the ranks of the unemployed. One way — the good way — is to get a job. The other way is to stop looking for work, either because you’ve retired, or become discouraged, or begun working off the books.

The yellow line on the left shows the official unemployment rate since 2008. It’s fallen from over 10 percent to under 8 percent. But the red line on the right shows the actual employment rate — that is, the percentage of working-age adults with jobs. What should scare you is that the red line has barely budged.

The economy is a lot worse than a glance at the unemployment rate suggests. And instead of doing anything to help those people get back to work, Washington canceled the payroll tax cut, permitted sequestration to go into effect, and is now arguing about whether to shut down the federal government — and possibly breach the debt ceiling — in the fall.

This is yet another consequence of the opposition party refusing to participate in governance.

Observer columnist John Naughton explains how the practices Edward Snowden revealed have hurt us:

[H]ere are some of the things we should be thinking about as a result of what we have learned so far.

The first is that the days of the internet as a truly global network are numbered. It was always a possibility that the system would eventually be Balkanised, ie divided into a number of geographical or jurisdiction-determined subnets as societies such as China, Russia, Iran and other Islamic states decided that they needed to control how their citizens communicated. Now, Balkanisation is a certainty.

Second, the issue of internet governance is about to become very contentious. Given what we now know about how the US and its satraps have been abusing their privileged position in the global infrastructure, the idea that the western powers can be allowed to continue to control it has become untenable.

His conclusion: "The fact is that Google, Facebook, Yahoo, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft are all integral components of the US cyber-surveillance system." And no European country wants to deal with that.

So, great. United States paranoia and brute-force problem-solving may have destroyed the Cloud.

New York Times op-ed columnist Charles Blow lays out the awfulness of "stand your ground" laws better than I:

Something is wrong here. We are not being made more secure, we are being made more barbaric. These laws are an abomination and an affront to morality and common sense. We can’t allow ourselves to be pawns in the gun industry’s profiteering. We are real people, and people have power.

Attorney General Eric Holder told the N.A.A.C.P. last week: “It’s time to question laws that senselessly expand the concept of self-defense and sow dangerous conflict in our neighborhoods. These laws try to fix something that was never broken.”

We must all stress this point, and fight and not get weary. We must stop thinking of politics as sport and spectacle and remember that it bends in response to pressure. These laws must be reviewed and adjusted. On this issue we, as Americans of good conscience, must stand our ground.

Well put.

According to a new study, it's because of poor impulse control:

It’s not that they are ignorant. Studies show that smokers are at least as informed as nonsmokers about the risks of smoking — and possibly more informed.

You might suspect, then, that smokers tend to be risk takers by nature. And some evidence suggests that smokers do take more risks than nonsmokers: they are more often involved in traffic accidents, less likely to wear seat belts and more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior. Women who smoke even have mammograms less frequently than their nonsmoking counterparts.

So what accounts for smokers’ risky-looking behavior? Our contention is that smokers exhibit poor self-control in the face of immediate temptation — which can look like a willingness to assume risk. (For instance, you might choose to have sex without a condom not because you are comfortable with the risk but because you are too weak-willed to bother with the inconvenience.)

I've thought a lot about the differences between rural and urban residents, including how more people smoke in the sticks. Smoking and carrying guns have something in common: they're nearly as hazardous or noxious to people nearby as they are to the people doing them. It's obvious, isn't it, that smoking stinks up the area, and having a gun makes you more likely to shoot someone else. Living in a dense city forces people, through legislation or social pressure, to behave in ways more appropriate to being around other people.

So, if people smoke because they have poor impulse control, yet we're obligated to issue at least some concealed-carry permits, we really shouldn't give them to smokers, should we?

Urban planner Pete Saunders, a Detroit native and Chicago resident, doesn't see many similarities between the two cities:

Chicago has a much larger and more diverse economy to draw from to address its debt concerns. A report from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis released in February shows that Chicago metro area GDP in 2011 was $548 billion annually, making it the third largest in the nation after New York and Los Angeles. That makes the Chicago economy nearly three times larger than Detroit's, which checks in at $199 billion. Chicago's economy is also more diverse than Detroit's, with no one industry sector making up more than 13 percent of the metro area workforce. Chicago's economy also enjoys demonstrated strengths in areas where Detroit is weaker — specifically, finance, transportation and warehousing, and education. There is simply a broader and deeper reservoir that Chicago can tap.

Perhaps more important, there are key historical differences that led Detroit to bankruptcy but kept Chicago on a growth path. Circa 1950, Chicago and Detroit were mid-century manufacturing doppelgangers — economic powerhouses teeming with industrial businesses, each with a bevy of skilled and unskilled workers to employ. However, governance differences caused their paths to diverge. Mayor Richard J. Daley is often remembered as the quintessential machine politician, but he cut his political teeth in fiscal policy before occupying the fifth floor at City Hall. He put that expertise to good use while in office. Also, the dozens of municipal corporations and special-purpose districts here, lacking in Detroit, meant the fiscal burden could be spread around. As a result, City Hall ends up having fewer direct responsibilities and a slightly rosier fiscal picture.

When Detroit doubled down on flinging its population into the suburbs in the last half of the 20th century, Chicago cleaned up. I remember the smog, dirt, and crime of the 1980s vividly—and the stunning clean-up in the 1990s. During the same time, Detroit emptied out even more.

Detroit shows just about ever method available for killing a city; Chicago shows the opposite. Urbs in horto is a reality.